Robert Barbour and Others

King Robert the Bruce

|

|

Great-grandson: Earl of Buchan ("Wolf of Badenoch")

|

|

Great-grandson: Alexander Stewart

(First extant Charter of Bonskeid and Coillebrochain 1494, First Laird)

|

Robert Stewart (inherited Bonskeid 1501)

|

|

John Stewart (4th Laird, murdered 1605)

|

|

John Stewart (7th Laird, rebuilds Bonskeid 1688 at Mains site)

|

|

John Stewart (10th Laird, farmhouse after another fire, accidentally killed in 1762)

|

Alexander Stewart (11th - doctor in Dunkeld and Perth, built house on present site)

|

Only child daughter Margaret marries Glas Sandeman

She known as Mrs Stewart Sandeman, they the Stewart Sandemans

(They get back Bonskeid after Alexander needs the money)

Margaret Sandeman marries George Freeland Barbour

He buys the house in 1857

Greatly enlarged 1859 and 1863 and looks much like now

|

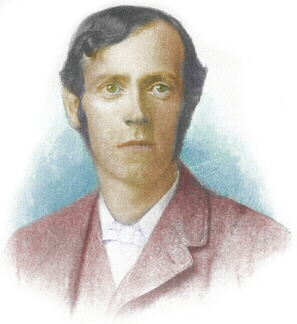

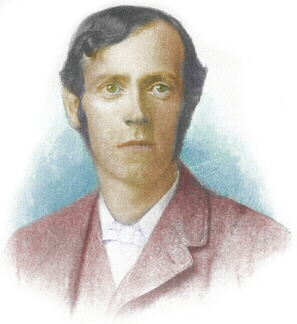

Robert Barbour (born 1854)

(after Freddy and Georgie killed on Manchester area railway)

Minister, dies in his 30's

|

Freeland Barbour (Liberal, interested in YMCA, dies 1946)

Moved to Fincastle, YMCA took over in 1921

Rebuilds stables, 1910 builds billiard room

|

Robert Barbour (becomes Reverend Professor Sir)

Sells Bonskeid House to YMCA 1951

(Son, Freeland Barbour)

|

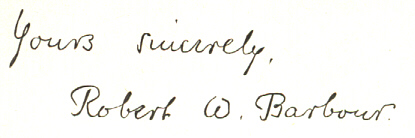

Robert Barbour 1854-1891

A short biography and writings

|

Born after his brothers were killed in the first operating railway accident (in Manchester, where George Freeland Barbour made his money), Robert's early life involved a close relationship with his grandmother Mrs Stewart Sandeman until she died in 1883. His parents created a strong religious setting for his upbringing in both Edinburgh (winter) and Bonskeid (summer). His mother also gave him a strong literary background. Growing up a shy, inward looking boy, something happened in a way of crisis which propelled his religious life. He broke out of the shyness and became a very successful scholar (except in maths) in Edinburgh and he lived within the Christian myth in a way that few would understand today. He knew of Darwin, but that impact was still building. Studying Theology with an intention to be a minister, he was aware of German scholarship including Schleiermacher (the theologian who can be regarded later as a groundbreaking "liberal"), and participated in learning this directly, if briefly, but he was quite traditional in his religion and the whole of his writing is steeped in this passing world view as indeed he was. Except he had one strong characteristic of that age: he combined an optimistic view of nature and his writing with his religion. It fits in with Romanticism. This assists his ecumenism too, no doubt, although he still prefered the Scottish Church for being essential in both what it rejected as well as in what it accepted. Steeped in this inheritance, and within it, he was as someone at the end of an age as the new one came in. He was also steeped in the Classics and Philosophy from his education. Again, this is something of the old world as the new of science was entering into the popular consciousness. So, this literary thinker (and it shows in the quality of his letter writing) was also very pastoral and practical in his ministerial work. He travelled through Europe (including Ireland), and in the wider world including South Africa, but he had pastoral ministries in Scotland. Altogether it might be said that, in nineteenth century gender archetypes, when to be scientific and progressive and rational was essentially to be "male", this scholarly man combined his view of rationality with many "feminine" qualities.

|

|

He was married to Charlotte Fowler, daughter of Sir Robert, twice the Lord Mayor of London. He visited Bonskeid often and after his father's death in 1887 their mother lived there. In 1889 they lived there briefly but moved on to a nearby property on land at Fincastle which had been broken up (between Sir Robert Colquhoun and the Stewart Sandemans) at the time of the financial crisis when Alexander Stewart was required to bail out his brother in law. He preached in the Glen of Fincastle, and refused to stand for Parliament preferring his religious life. He did want to go to China in mission work but was unable to do so as illness took hold. He did get to teach Church History at Glasgow College, and students from universities' missionary societies (of many denominations) came to Bonskeid, but he never began teaching in Edinburgh because of the illness. In February 1891 he travelled to France in a futile attempt to prolong life, to Mentone, where he was very weak, and then Aix-les-Baines, where he died, and his ashes were buried in the West Wood at Bonskeid alongside his child Robin and his father, and his mother was buried there a few months later.

|

|

Thus the Christianity of his parents became his life and work, and this has continued on since. The Barbour family still own land around the current grounds of Bonskeid House, and the current Robert Barbour ministers still at Tenandry Free Kirk.

|

|

Below are some of the writings of Robert Barbour from the nineteenth century.

|

Unto the Hills

Schiehallion clearing from her snows - the sight!

You fancy how she stretched one seamless sheet

Daily the sun into diamonds beat

And every evening to red rubies smite,

Till 'twixt the flakes at foot, grown faded quite,

The heaven's and heather's answering eyes did meet,

While the robe rose from her far-planted feet,

Crept to the shoulder and past, one crown of light,

So have I witnessed some immortal theme

Rise on the mind and have the mastery,

Perfect and in one piece without a seam,

Challenging all and always conqueringly,

At length shot through by a superior gleam,

And it and all the heaven see eye to eye.

|

Bei Herrn Pfarrer Pressel,

Lustnau, Tubingen, Wurtemburg, 1876

|

[...] At eight o'clock we adjourned to Teuffel's class (the Principal's), whose Latin history was a text book of mine, and for a dreary hour heard him lay down the pros and cons of Homeric unity with all the regularity, but little of the itnerest, of the array of combatants in the Trojan War. He made a very inferior Fate indeed, and seemed afraid to say anything himself, while unsparing to the combatants on either side.

|

|

After him, we trotted off at nine to the Stift (Educational Institution) to hear the great Sanskritist, Roth, lecture on the universal history of religions. He knows Muir well, from whom Smith has an introduction to him. The subject was the first beginnings of religion among the early Aryans; he spoke distinctly, hand in pocket, and looked like an improved version of John Stewart, who built Bonskeid. The class is very large; we notice the desks cut with the favourite feminine names of the German students; but, except for that, there was nothing to distinguish it from home. The students hang their caps at the door; the professor wrote out hard names on the balck board; there was no fussing, but the utmost order prevailed.

|

Tübingen, Würtemberg, July 26, 1876, 11 pm

|

My good angel turned up in the form of a half invalid Balliol man (between Mods. and Greats) who wanted a companion in the Black Forest. So, as my only hearty friend in the house, the Frank, was down with heart disease (a result, I believe, of desperate attempts to instil the irregularities of the language into said Englishman's thick head, you will add, that of somebody else as well), I accepted; and leaving Beck up to the waist in Baptism (he was just emerging, and that gloriously, when I picked him up again to-day), Diestel deep in the 4th "I-v-st" of Genesis, and class wrestling with Schleiermacher's notion of Immortality, I got into the open air. I can never hope to tell you what a time we had. For the first moment since coming here, I got really free from my cold; the weather was wonderful; and the walking ground even more than we had imagined.... |

|

[...] |

|

To attend to the solemnities. Hebrew is buried; Schleiermacher and Beck are being waded through, with skippings over Schiller and Lessing (the former of whom turns poor after some reading); the lectures are easily followed now. Roth is extremely interesting upon the remains of the Celtic religions, while Weiszzäcker is retreating with the Gospel of John to about the year '90. After all, the world is improving and men with it. I intend to take a month's grind at pure philosophy when I get back (D.V.) and then another at mixed Theology. |

|

After all, I shall be sorry at heart to leave this old place, spite of its much imperfection, and more failure on my side. I am beginning to believe that the heights where your last and higher effort leaves you, are the very spots (the only ones perhaps) where you get lifted up; and that there is no point of worked-out inspiration that does not hold wings to something higher; and that all such experience is spiritual.

|

Springland, June 4, 1879

|

I have just been to grandmamma. On a little table by her bedside lay a great, glossy-backed, brown book, with faded guilt edges. She gave it to me. It was her mother's, Miss Oliphant of Gask, eldest daughter of the house, and elder sister of Carolina Oliphant, Aunt Nairne. Her mother, you know, married Dr. Stewart of Bonskeid, and grandmamma was their only child. Her mother brought this Gask Bible away with her on her marriage, and out of it and the Book of Common Prayer bound up with it, she taught her child, Margaret Stewart of Bonskeid, reading every day the Psalms, and every Sabbath the Service, so that grandmamma was reared in the English church (a strict Episcopalian), and in those daily lessons from this book she learned first the marvellous acquaintance with Scripture which she has. She never loved the Episcopal Church, and after her marriage and conversion joined the Presbyterian Church and 'came out' at the Disruption in 1843 into the Free Church.

|

|

I must tell you something about Springland. It is a lovely little place, a mile up the Tay from the town of Perth, with beautiful, simple grounds, and a tower built on the river (the mark for boat races) overlooking the Inch, where the battle in the "Fair Maid" was fought; in that tower the 'schöne Magd' herself, my mother, as the towns-folk fondly talked of her, taught for years of unconscious waiting a little school of children, while my father was building up his business and a stainless name in Manchester. Such a funny mixture it is - to come of high chivalry, poetry, Jacobitism and Episcopacy, hard work, strong sense, Lancashire cotton and Presbyterianism - such is some of what has gone into the making of me. And from this door the mutterlich-gesinnte herself (for she had brought up a whole army of brave boys, managed a high-spirited mother, and been submissive to a strict, resolute-minded father) was married away thirty years since, to begin a life of suffering and deliverance, of succouring others and succour sent from God, only second to grandmamma's. I feel almost 'to inherit' too rich 'a blessing.' There have been clouds gathering in every quarter of my heaven for a hundred years, since my great grandmother, Marjory Oliphant Stewart, began to lead an invalid's life in a little house in town here, and retired every day at noon for an hour to pray for her place of Bonskeid, for her child Margaret Stewart, and for everyone who should ever come of her house or come into it.

|

Auckland Castle, Bishop Auckland, April 29, 1882

|

[...]

|

|

...how beautiful a thing the bishop's household life is, and saying in so many words wherein its beauty lies.

He calls these lads [students who reside with the bishop] (and I can imagine worse things to feel myself, for the nonce, one of them) his family, and they treat him as frank, ingeneous gentlemen's sons would treat their father. He is accessible to their difficulties and their doubts, if they have any; but, a thing more remarkable, he is open to all their kittenhood of mirth and fun. To hear him alone with them is to feel you are on the edge of a circle, which tempts you almost to stand on tiptoe and look over and wish you were inside. It is a searching trial of true homeliness, to observe how it comports itself when there are strangers present. But I assert my coming in has not bated one jot of all this family joy. Last evening after prayers, they were poking fun at the bishop. One man was asked how he was getting on with Hebrew. The fellow boldly turned the weapon round by asking whether his lordship was prepared to teach him. Dr. Lightfoot was gently demuring, when someone else burst in, as if with a child's impateince and fear of some older uncompleted promise: "No, not before we have these lectures on botany.." Then, assuming the air of someone to whom that study was even as his necessary foot, he went on to report his observations, taken daily on his walks to and from the district, of two interesting weeds. It sounded like a clver parody upon Darwin and his climbing plants trained up the bed-post.

|

Edinburgh, January 22, 1884

|

[...] |

|

I had a long talk with K. upon his book (translation of Schopenhaueer - the Pessimist - kind of modern Buddhist), and upon his own views. He gave me some hints about how one needs to preach the goodness of the unseen, not as a future after death, but as a present possession - something above us which may be in us now. That, of course, is just what Jesus has been saying for two thousand years: "he that hath faith hath everlasting life." One must not preach the hereafter only, especially to those who feel (like the young) the livingness, and greatness, and earnestness of the now. But neither must one forget that other word, so often repeated after thos I have quoted: "and I will raise him up on the last day." For aged, for outworn, for laden souls, for dying and bereaved, ay and for children lately come from the other land, that also is God's truth...

|

Bonskeid, April 14, 1886

|

[...] |

|

At 11.30 Mr Ritchie came, and we climbed the hill together to the Mains... The Glen was looking lovely, the young larches just breaking into green, and the hills quite royal in their purple... We walked back by the new drive. The riverside was sunny and warm as June... At 3.30 we drove down by the Falls to look at the new plantation there... At the bridge Robert Mackintosh and I came from the dog-cart and walked home by the footpaths along Garry and Tummel. It was a lovely afternoon. The mottled bed of the Garry showed brightly through its flowing stream; while dark Tummel in its full strength went hurrying down and "leapt his falls with thunder than glee." It was alomost terrible to sit at the Queen's Seat and watch the frothing water sounding by. The background was unusually striking. The Giant's Steps stood out behind in black profile against the sinking sun, while clouds of spray curled up in front like incense steaming from an altar. |

|

All the way home was one wonder of bare birches; their delicate foliage full of sunlight, shaking like fairy veils in the faint blowing wind, and their straight stems flashing like spears of silver out on the hillside. I never knew Bonskeid more beautiful.

|

Bonskeid, August 26, 1887

|

[...] It was a strange, still afternoon - everything covered with a blue-grey mist. At the Queen's View (4.15-20) I got off, and led Norma near to the edge of the rock, and had a quiet glance at the weird landscape. Land and water lay under the same heavy veil of vapour, reed-beds and glassy levels and jutting promontories, standing distinct, yet dim, in their gauzy dress. The very heavens were thickly draped and curtained, so that Ben-y-Vrackie, behind me, loomed faint and spectral against the sky. Only above Schiehallion the mist was caught aside, and a slight suffusion of red showed the grand mountain in its simple strength and massiveness.

|

|

Gently descending the hill, I felt the rich fragrance of the birchwood on Borenich, doubly rich with all the drought and heat of this tropical summer, and ready to exhale with the slightest moisture. I passed the farm at 4.40, and beyond Croft Douglas had a minute or two's chat with a lad, carrying fowls to market, to whom I gave a threepenny-bit to carry the fowls head-upmost for the rest of the way. That was at a quarter to five - an hour from starting - and at five minutes past five I made Loch Tummel Inn. A little girl at a cottage beyond gave me some water in a tub for Norma, who said she could go no further till this want was supplied; indeed, she nearly carried me into the cottage in order to emphasize her feelings on the subject. So we went through the close wood of Portneilan, and, emerging from it, caught the full blow of moorland air off broad Rannoch and lofty Schiehallion. How I drank it in!

|

|

The last three miles we did in twenty minutes, for I was getting anxious about my time. As we flew along, I was only aware how the scents kept changing. Rich aromatic birch, with bog myrtle among it, rose from either side as we slanted down from the heights above the loch to the river-level again. Then came the open moor, with honey-laden heather in full bloom, among grey rocks and stones on the one hand, and on the other the wide-ranging Tummel beginning to race and and grumble again with the narrowing glen.

|

|

I arrived at my destination, a little way beyond the peaked bridge on the Rannoch road, at 5.25.

|

Bonskeid, April 9, 1890

|

Everything is bursting and breaking and sounding with young life; starlings and 'merles' were crying in the oaks above me; doves, pairing, fled like surprised lovers from a spruce close by my side; rabbits set off before me with the peculiar hop, step and jump they only put on in spring. Every tree and branch and twig wore a favour different to its fellow, that looked as if it had never been worn before. It is God's world, and He still stays in the hearts of those who keep His commandments, It is very good.

|

Royal Hotel, Edinburgh, August 19, 1890

|

I have been much in spirit to-day at Newman's burial. How little his later associates seem to have found in him! I can hardly credit the reports of their sermons, they are so utterly inane. It confirms the opinion I have always held, that his creative period lay almost wholly within the years before he joined the Church of Rome. |

|

Hutton's eulogium was not unworthy of the writer. But how false any unqualified admiration sounds from the lips of a Christian man... |

|

[...] |

|

Ah, père Newman, if we could only learn of the Third Person in the Blessed Trinity, each by ourselves, and all together in the Church Catholic, to worship the Holy Ghost; even as we learnt of Him, by thee, to worship the unbegotten Son! |

|

I am not a theologian, nor the son of a theologian, but I am beginning to be able to adore the Spirit equally with the Father and with the Son. It is a wonderful and blessed thing to do that. We must not speak much of it; but we must try to do it, and do it more.

|

Excerpts from:

Barbour, Robert W. (1893), Robert W. Barbour: Letters, Poems and Pensées, collected for private circulation, Glasgow: University Press, 'Preface' by Henry Drummond, 'Memorial Chronology' by James Stalker. Available in the YMCA Bonskeid House Library.